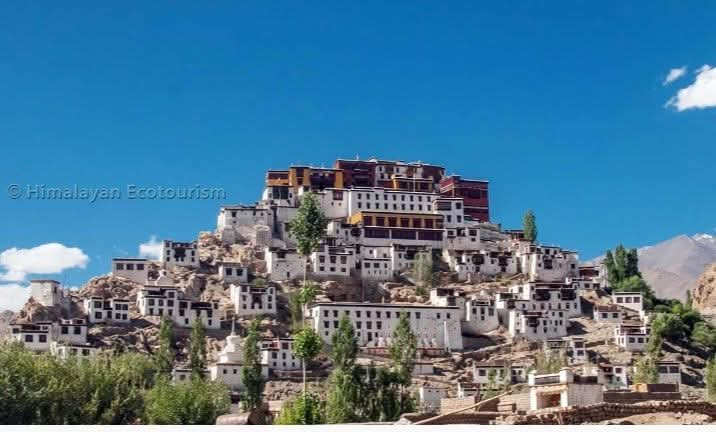

Ladakh at the Crossroads: Autonomy, Identity, and the Promise of Democracy”

The above picture has been taken from “Himalayan Ecotourism”

SHUBHAM ARYA, LAW GRADUATE

Notifications from the centre greatly aid in meeting people’s needs. Since 2019 and the division of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir, the leaders of the Union Territory of Ladakh have called for constitutional protections for land ownership, economic opportunities, the preservation of tribal cultures and languages, and a more representative government. The task at hand is to further develop representative democracy. All of these demand clusters have their roots in the region’s distinct historical and demographic makeup, and it was promised, both explicitly and implicitly, that they would be addressed when Article 370 was repealed. The central government’s notifications earlier made a big difference in addressing many of Ladakh’s requests, particularly those pertaining to quotas, protection, domicile-based government positions, and language promotion. Although these directives are welcome, they should be followed in due course by actions that guarantee a strengthening of Ladakh’s representative democracy and allay some of the concerns around land rights. A residency requirement for government employment is introduced by the Ladakh Civil Services Decentralization and Recruitment (Amendment) Regulation: A person must have lived in Ladakh for 15 years or taken the UT’s Class X or Class XII exams in order to be eligible. With the exception of the EWS quota, the Union Territory of Ladakh Reservation (Amendment) Regulation has set a maximum of 85% on reservations. This effectively gives residents of the UT (which has a 90% Scheduled Tribe population) almost complete reservations. Along with facilitating additional methods for promoting and safeguarding the region’s culture and legacy, the Centre has also recognized English, Hindi, Urdu, Bhoti, and Purgi as official languages of the Union Territory. The majority of people speak Bhoti and Purgi, and there has long been a call for their long-overdue recognition. It is undeniable that the military and the Centre have had, and will continue to have, a strong interest in and presence in Ladakh. From the Kargil conflict with Pakistan in 1999 until the border conflicts with China from 2020 to 2024, the UT has been a military flashpoint with both China and Pakistan. Large tracts of land in the area are also crucial for the nation’s renewable energy objectives. However, these requirements cannot override democracy’s fundamental tenets. Many Ladakh residents demanded that the region be added to the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, which grants considerable autonomy, much like areas of the Northeast. Through its directives, the Centre has attempted to offer protections. However, it doesn’t appear to have addressed the call for limitations on foreigners’ ability to own land. A wider delegation of authority to the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils (LAHDCs) is much more obvious in its absence. These municipal elected bodies currently have limited administration and no legislative authority. Ladakh requires some kind of representative administration, much like the rest of the former J&K state. Giving its citizens a voice should be a top priority as the Centre and the local leadership discuss the next stages for the UT’s political architecture.

The constitutional validity of the recent 85% reservation policy in Ladakh, enacted by the Central Government via the Ladakh Reservation (Amendment) Regulation, 2025, stands to be challenged against established constitutional and judicial precedents. One of the strongest points is its conformity with the Supreme Court’s judgment in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992), where the Court squarely ruled that the reservations under Articles 15(4) and 16(4) ought not exceed 50%, except in “exceptional circumstances”. This rule has been reaffirmed by subsequent Constitution Bench rulings and forms the law of the land under Article 141 of the Constitution. The Ladakh law, which prescribes an 85% reservation (not counting the EWS quota), openly violates this judicially set ceiling unless it has a justification based on extraordinary circumstances.

The “extraordinary circumstances” concept has been construed strictly by courts. Tamil Nadu, for example, has traditionally had a reservation percentage in excess of 50% relying on proven historical and social backwardness, evidenced by extensive data and legislative measures. By contrast, Ladakh’s population—albeit largely tribal—and the governance gap in the wake of the repeal of Article 370 perhaps might not, on their own, be sufficient to constitute such extraordinary reasons for that reason especially when the region is not brought within the sheltering umbrella of the Sixth Schedule. A second main concern relates to the source of power for making this rule. The Central Government relied on Article 240 of the Constitution, which entitles the President to make regulations for Union Territories where there is no legislature. Though the provision gives broad executive discretion, it cannot be read to enable the flouting of constitutional norms, particularly those established by the judiciary regarding fundamental rights and equality. It is a well-established doctrine that no executive action can supplant the Constitution’s basic structure or judicially construed restraints on state authority.

Based on the above, the amendment to reserve Ladakh is likely to undergo judicial review. Petitioners will contest the rule on the basis that it contravenes the 50% threshold in Indra Sawhney, fails to have enough empirical grounds to be recognized as an exceptional measure, and negates the equality principle. The government, in turn, can contend that Ladakh’s special demographic composition—being more than 90% Scheduled Tribe—and the requirements of maintaining indigenous rights and representation after the abrogation of Article 370 are reasonable reasons for departing from the rule. Yet if this defence can survive narrow constitutional scrutiny is also doubtful and will depend on the Supreme Court’s definition of “extraordinary circumstances” in the particular case of Ladakh.

SHUBHAM ARYA

Courtesy Photo : Himalayan Ecotourism

(THE ABOVE VIEWS IN THE ARTICLE ARE PERSONAL OF SHUBHAM ARYA, LAW GRADUATE AND UKNATIONNEWS IS NOT RESPONSIBLE )