Sunderlal Bahuguna: A Conscience in the Mountains – Between Ecological Ethics and Human Contradictions

On the birth anniversary of Sunderlal Bahuguna

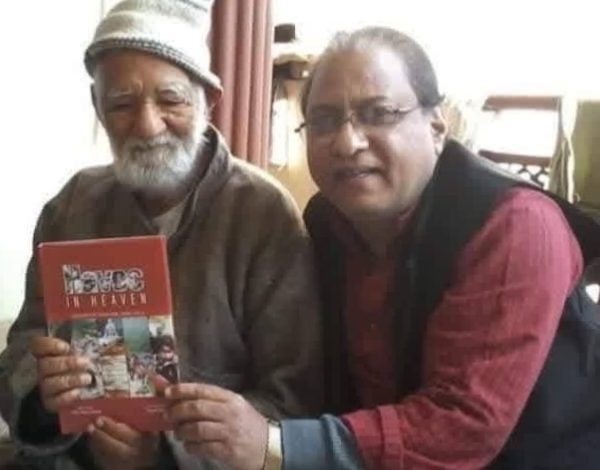

Contradictions in Sunderlal Bahuguna’s life do not diminish him; they humanise his philosophy of life, says SURESH NAUTIYAL Greenananda

Sunderlal Bahuguna was born on 9 January 1927 in the princely state of Tehri Garhwal, ruled by the Shah dynasty and lying outside British India. He passed away on 21 May 2021 in Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, leaving behind a life that profoundly shaped India’s environmental consciousness, moral imagination, and the unfinished journey toward Green Politics.

When Bahuguna was born, the Himalaya were not described as “fragile ecosystems.” Forests were valued as timber, rivers as potential energy, and mountains as barriers to economic growth. The modern Indian state would later inherit and intensify this extractive imagination. Bahuguna’s life unfolded as a sustained ethical challenge to that worldview, asking a question India still evades: What kind of development preserves life, and what kind destroys its own foundations?

Though raised in a princely state, Bahuguna entered India’s freedom movement and absorbed Gandhian principles of simplicity, non-violence, and moral persuasion. After Independence, his work turned toward social reform—combating untouchability, resisting caste discrimination, and educating villagers in their own cultural language. He spoke not as a technocrat but as a people’s educator, using Garhwali idiom, folk memory, and lived experience.

This formative phase is crucial for understanding Bahuguna’s later ecological politics. For him, social justice and environmental protection were never separate struggles; both were rooted in dignity, restraint, and decentralised community life. Standing beside him throughout was Vimala Nautiyal, his lifelong companion and collaborator, whose intellectual and organisational labour remains insufficiently acknowledged. Any serious remembrance of Bahuguna must also remember her.

Bahuguna’s originality lay in framing ecology not as a technical problem to be managed, but as an ethical relationship between humans and nature. Long before environmentalism entered state policy or global conferences, he warned that Himalayan ecosystems were finite and vulnerable, and that reckless extraction would produce social collapse alongside ecological ruin.

In this sense, Bahuguna anticipated the philosophical core of Green ideology: that development divorced from ethics is a form of violence, and that economic growth cannot be allowed to override ecological limits or community rights.

The Chipko movement brought Bahuguna national and international recognition. Villagers—most notably women such as Gaura Devi—embraced trees to stop commercial felling, transforming protest into moral action. Chipko was not merely resistance; it was an awakening of ecological consciousness rooted in community survival.

Yet Chipko’s history is collective and complex. Bahuguna was not central to its earliest moments, which emerged from women-led Reni village action. His key contribution lay in carrying the movement beyond Uttarakhand, translating a local struggle into a national and global ethical narrative. Whether one centres or marginalises his role in Chipko, it remains true that Bahuguna’s environmental commitment preceded and extended far beyond this single movement.

The most defining—and contentious—chapter of Bahuguna’s life was his opposition to large dams, especially the Tehri Hydro Project. He warned that such projects would submerge villages, displace communities, destabilise fragile geology, and silence living rivers. His resistance culminated in one of the longest fasts in post-Independence India, lasting over 56 days.

The dam was ultimately built. Tehri town was submerged, and thousands were displaced. In conventional terms, the movement failed. Yet Bahuguna’s struggle was never about victory alone; it was about creating a moral record. Today, as landslides, floods, and climate disasters intensify in the Himalaya, his warnings read less like idealism and more like foresight.

Beyond dams, Bahuguna supported women’s struggles against deforestation and liquor mafia, stood with the Beej Bachao Andolan (Save the Seeds Movement) to protect seeds and food sovereignty, and undertook the Kashmir-to-Kohima foot march to articulate the Himalaya as a single ecological and cultural continuum. His politics was embodied—carried by walking, fasting, speaking, and listening.

Yet this approach also exposed a structural limitation. Bahuguna remained deeply sceptical of formal political organisation. When urged to help build a Green political alternative, he once remarked, “Give me 100 Green activists, I will make a difference.” The statement reveals both insight and hesitation: An understanding of collective power, coupled with a reluctance to institutionalise it. In a democracy where movements often dissipate without political structures, this hesitation may have cost Indian environmentalism a historic opportunity.

Bahuguna also played a quiet yet significant role as a journalist, using the power of words to reach far beyond the mountains he inhabited. As a stringer for Hindustan Hindi and the Hindi Service of the United News of India (UNI-Varta), he reported from remote Himalayan regions that were otherwise absent from the national media gaze. This journalistic engagement gave him an additional public platform — enabling him to communicate local struggles, ecological concerns, and people’s voices to a wider audience across India. Journalism, for Bahuguna, was not merely a profession but an extension of his ethical and activist commitment: it helped translate grassroots realities into public discourse and connect marginalised hill communities with the larger democratic conversation.

An honest assessment of Bahuguna must also confront discomfort. He accepted state honours, including the Padma awards, choosing not to use refusal as a political statement. For many radical environmentalists, this signalled accommodation rather than resistance. More controversially, after the submergence of Tehri, he accepted state-allotted housing in place of his riverside hut—an act critics viewed as morally inconsistent with his opposition to displacement.

There were also allegations that, in earlier years, he had worked as a timber contractor involved in tree felling. Whether exaggerated or partially true, such claims complicate the narrative of seamless moral evolution. If true even in part, they suggest transformation rather than hypocrisy—but this transition was never publicly theorised by Bahuguna, leaving room for contested memory.

Others criticised his closeness to power, his preference for dialogue over confrontation, and the way collective movements—especially Chipko—became associated with his individual image. These critiques reflect deeper tensions within social movements: Between visibility and representation, leadership and collectiveness, ethics and power.

These contradictions do not diminish Bahuguna’s legacy; they humanise and sharpen his philosophy of life. He was not a saint outside history, but a moral actor navigating pressure, recognition, compromise, and uncertainty. His life exposes the central dilemma of Green Politics in India: How to move from ethical protest to durable political alternatives without losing moral ground!

On his birth anniversary, Sunderlal Bahuguna should be remembered not as an unblemished icon, but as a conscience that unsettled power while remaining rooted in restraint. He reminds us that ecological destruction always travels alongside social injustice, and that the poorest and most rooted communities pay the highest price.

In an age of climate crisis and ecological amnesia, Bahuguna stands as both memory and mirror. To remember him is not to ritualise his image, nor to erase his failures, but to re-enter the unresolved questions he posed. The Himalaya still echoes those questions. The rivers still carry his warning: Protect life first—politics, economy, and progress must follow.